Inspirational (1)

I was inspired to write this post by another blog post about … inspiration. As is so often at the moment, it was the poet Julie Mellor. You really should follow her blog. Here’s the link. I want to quote a chunk of the beginning of the post:

“This morning, checking my emails, feeling guilty about not writing, feeling anxious about not having anything to write about, suddenly, starlings descended, all at once and on the same tree, the black elder, Sambuca Black Lace, its leaves thinned by the cold and the wind, its berries black and ripe and taut as eyes, and the starlings hit it with their bodies and pecked as though it were alive, a baited thing, and berries were grabbed and swallowed and berries fell on the stone flags where more starlings jostled and snatched and I’d been at such a loss to begin anything and using the emails as an excuse that when the starlings came I rushed for my camera with the intention of photographing them for my blog, though when I approached the patio doors I startled them and they grabbed their things and ran, but it was a moment of clarity, when time slows and you’re pulled into something which is not your life.”

I’m not thinking right now of inspiration as a eureka moment. But I will next week, and not least because of this post. Thank you Julie.

What I am thinking of is, how difficult it is to describe. I think that one kind of inspiration is a slow-burning business that you only grasp in retrospect. Sometimes a long, long retrospect. I think it involves two key elements, encouragement (and the hope and self-belief that engenders) and (crucially) example. Kim Moore and Gaia Holmes tick both boxes for me. I’ve talked before about their encouragement (and to save them embarrassment, I think I’ll try to stop writing about it) but not about their example. They are both incredibly hard-working, they practise their art and craft, they are absurdly modest, they are both great readers of their own work, they are always looking for the next step, they are self-critical, they seem to absorb everything … that kind of example. Anyway. Here we go. My inspirations, in chronological order.

"Who’s that bloke?"

"That’s Max Harrison’s daddy."

"What’s he do, then?"

"He doesn’t do anything. Ee’s a poet."

I’ve dined out on that story, but the point is that though contemporary poetry meant absolutely nothing to me, then, I mentioned this to a colleague, who invited Harrison to come and read to our third year B.Ed English students, and so it was that I went to my first ever poetry reading.

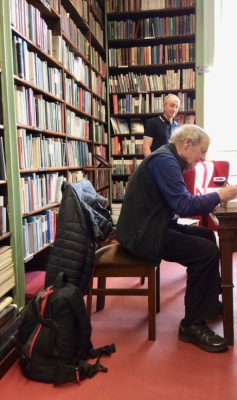

Only about eight students turned up that evening, so we used the staff common room, sitting in a circle of comfortable chairs, and Harrison (trademark greatcoat and all) sat on a sofa, and read.

He read along with his trademark lengthy introductions to many poems. He read with a compelling intensity, flattened Leeds vowels, and exact consonants. He read from Loiners (the collection that his mother had thrown on the fire and then snatched back, realising it was a library book); he read 'Thomas Campey and the Copernican system', the poem about the crippled bookseller in Leeds Kirkgate market from whom a young Harrison would buy all sorts of esoteric (to me) stuff: Mommsen, Spengler, Gibbon. He read 'The nuptial torches' and the hairs on my neck prickled as he made the flames of the auto da fe crackle in a hushed staffroom. Above all he read 'National Trust', which then was still a handwritten draft in his notebook, and he told the backstory of the Edale gentry lowering a prisoner from the local lock-up down the shaft of a cave to find out how deep it was. It was only later I learned the craft of it, this immaculate blend of demotic English, linguistics and scholarship, and the elegance of its complex rhyme scheme …this 16-line sonnet that became another Harrison trademark. And I have never ever forgotten the last lines:

mes den hep tavas a-gollas y dyr

(Cornish) ‘the tongueless man gets his land took’

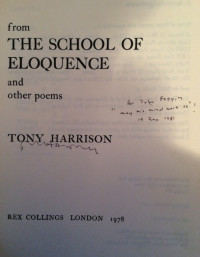

My signed copy of From "The school of eloquence" and other poems is arguably my most treasured possession (family not included). So. Thank you, Tony Harrison. And, of course, you have no idea.

That’s thing, isn’t it? Some years ago the Education section of the Guardian had a regular column called My Inspiration. Its editor then was Emily Moore. Emily, I owe you a thank-you. Invited famous folk would nominate a teacher from their past as their "inspiration".

The novelist Jill Dawson nominated me. What struck me then, and still does, is how different her and my perception of that time are. I genuinely had no clear ideas about what I was doing with this first-ever A-level group at an almost brand-new school. I wasn’t short of ideas. They just weren’t clear. But Jill Dawson says that I made The Waste Land make sense. If that’s true, we must have discovered it at more or less the same time. It was simple enough. If you treat it like music and hear it aloud and perform it, then it makes beautiful emotional sense. But in truth, I wasn’t all that aware of Jill except as an absorbedly, perceptively quiet, rather private student. A dark watcher. Yes. But apparently I made some kind of process possible. Just as Harrison did for me. By accident. Anyway, it’s payback time.

I was writing in an earlier post about how hard it can be to find a way of imagining people - not inventing them (that’s for novelists) - but realising their otherness. Jill Dawson sent me copies of all her books, each one signed with a different message.

They are my most treasured possessions, too. I was trying to write sequences about 19th century painters, and about soliloquising statues. And in came one book especially. 'Fred and Edie'. One reviewer wrote: "Flaubert would have loved this story. I certainly did."

Jill takes the story of the (then) notorious murder of the husband of Edith Thompson by her younger lover, Frederick Bywaters. Both were hanged in 1922. She takes the story of this folie a deux, which interweaves the imagined voice of Edie in her prison cell, with real and imagined letters sent to her ‘Darlint’ Fred. What captured me was Jill’s ability to inhabit the voice of Edie, with all her cultural and social aspirations and self-consciousness and vanities, the way she caught Edie’s linguistic tics and small pretentions: How much more interesting life is when one has occasion to write about it, says Edie. That one stuck. And still does. It’s impossible to do justice to the delicacy of what’s achieved in this novel. You’ll have to read it (There’ll be a full bibliography at the end; reach for the PayPal button now).

But I can’t not point out that one of the introductory epigraphs for the story is from The Waste Land, and one of my favourite bits too:

You gave me hyacinths first a year ago; they called me the hyacinth girl

I think I might have gone on a bit about that, to my sixth form group. And one more thing about inspiration. I suspect there’s a thread of envy in there, too. Why can’t I do this? Why don’t I do this? Well, I will. So, thank-you, Jill Dawson; ventriloqual novelist par excellence. My inspiration.

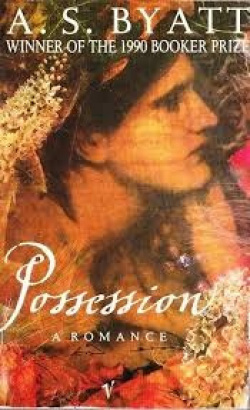

One is the sheer sensuousness of it all. I’ve never read anything with so much colour and texture. It’s incredibly rich and visual and tactile, but always in the service of understanding the characters and their intense, sometimes heartbreaking relationships. It’s one of the few novels that can have me in tears. What about the garden full of roses, swarthy damask, thick ivory, floating pink …fantastic spotted lilies, curling bronze and gold, bold and hot and rich?

This told me what I might be after with my pre-Raphaelite painters, as does her description of a photograph of Randolph Ash:

thickenings and glimmerings in the black … the beard, a riverful of silvers and creams, whites and blue-greys, channels and forks

I know an English teacher who was so persuaded of Ash’s historical reality that she asked for his work at the University in Leeds. But more important was the impact the book had, about the same time as Jill Dawson’s Fred and Edie.

While Jill Dawson taught me to listen carefully for the tics and nuances of speech and the way you might capture them in writing, what Possession did was to show me the importance of absorbing, really absorbing, how texts work, how they’re put together. Think about what Byatt does in this novel. She creates persona after persona. She writes their letters; more than that, she writes their correspondence. She writes their journals and diaries. She does pastiches of academic criticism. She invents autobiographies written by other people. She writes her character’s invented tales and poetry, Christabel’s fairy stories, her mini-epics, Ash’s ventriloqual dramatic monologues, Christabel’s lyric poems - like Emily Dickinson - and she can do all that because, as she says, she has immersed herself from childhood in Victorian poetry (as well as everything else … she’s got a frightening range of reference as well as an acute ear and a painter’s eye). And what she taught me is that you have to work, you have to read and read and read. And listen to poetry, its complex syntax and lexis. You learn from the company you keep. Thank you, AS Byatt.

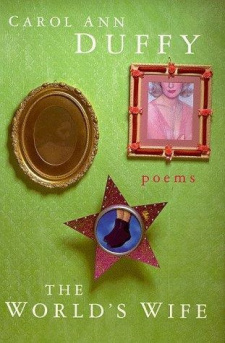

"Girls, I was dead and down / in the Underworld"; 'Eurydice' gets an urban edge. The inspirational example I took from this collection, though, was to see how a sequence of poems could be crafted from borrowed identities through which you could discover how you thought about the world, and, perhaps, how the world saw you.

If I could only have one poem from the collection it would be 'Little Red Cap'. And if you want to know why, then sit and copy it out by hand, several times, and be delighted by the discoveries you keep making about the craft of writing. Like I say, I’ve never met Carol Ann Duffy, though I know she’s read some of my poems because I’ve put them in for competitions she’s judged. But I don’t hold it against her. Thank you, anyway, Carol Ann.

There you are then. Four inspirations and a labour of love. Four people who teach me in so many ways that nothing is real till it’s named, and that’s what poetry is for.

As Christabel la Motte (who is, after all, a poet made completely of words) writes in a poem that is, after all, only imagined:

The first men named this place and named the world;

They made the words for it; garden and tree,

Dragon or snake, and woman, grass and gold

And apples. They made names and poetry

I think I should set homework. What and who are your inspirations? Answers in the Comments box at the end of the page, please. Thanks for your time. Next week I’ll be riffing further on inspirational people and texts ... especially non-fiction texts by non-poets.

Bibliography

Jill Dawson: Novels, all published by Sceptre: Trick of the light [1996]; Magpie [1998]; Fred and Edie [2000]; Watch me disappear [2006]; The great lover [2009]; The tell-tale heart [2014]

As editor, all published by Virago: How do I look [1990]; The Virago book of wicked verse [1992]; The Virago book of love letters [1994]

Poetry: White fish with painted nails [Slow Dancer Press]